The arrangement did not work; the Xiongnu kept on raiding the empire's borders, nimbly outmaneuvering the Chinese infantry and heavy chariots.

After a report from minister Chan Cuo in 169 BCE, the Han in response started to create their own cavalry force and set up a breeding program for horses.

They even sent a mission to the Ferghana valley to get access to the semi-mythical 'Celestial Steeds' that lived there, though the expedition was a failure.

Shortly after emperor Wu ascended the throne, the Chinese went to the offensive.

In 133 BCE the Han, in the spirit of warfare as described by Sun Tzu laid an ambush at the Battle of Mayi,

which failed and the battle never took place.

In the next years there were several other skirmishes.

Between 129 BCE and 119 BCE the Han launched their first full-scale military campaigns into the heart of Xiongnu territory.

After some initial losses, they defeated the nomads in a several battles, took prisoners and drove others northward.

Efforts were made to solidify the territorial gains: native Xiongnu were replaced, Han settlers moved in,

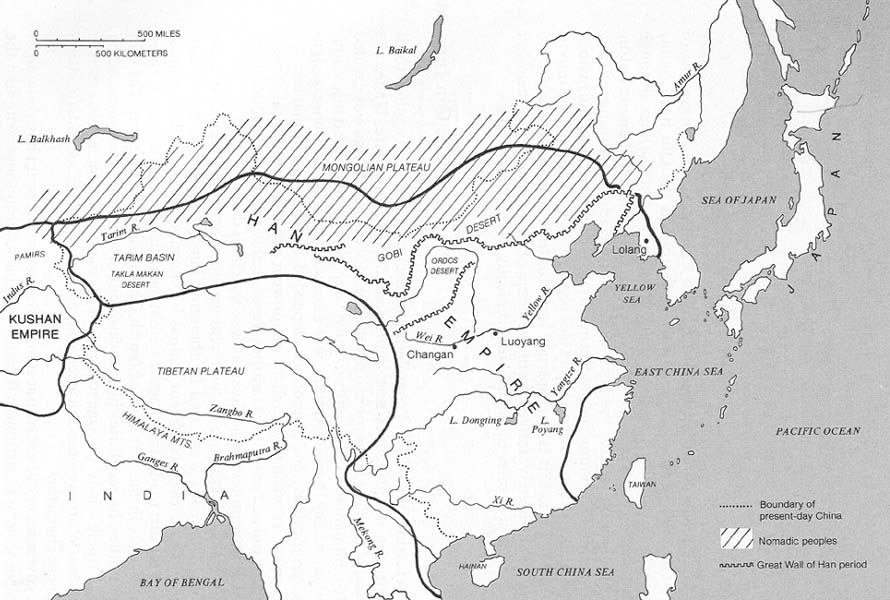

the Great Wall of China was extended and fortified frontier towns were established.

Border areas were reduced to vassals.

The operations had the side effect of opening up the famous silk road, over which merchants could conduct trade between China and the west.

But the real objective was to deny the Xiongnu the resources of the oasis cities along the road.

After 100 BCE the Han campaigns met several severe defeats and for a time there was a stalemate.

Fortunately for the Chinese, in 60 BCE civil war broke out among the Xiongnu, who for several years fought with everybody and themselves.

Eventually, in 54 BCE the confederation split into two halves, east and west.

This weakened them.

The Western half briefly subjugated the Wusun and other nomad peoples, then collapsed.

The Eastern Xiongnu withdrew behind the Ordos river, though later recovered and in 18 BCE pushed the Han back once more.

For almost a century the balance shifted back and forth between the nomads and the Chinese.

Gradually the position of the Xiongnu weakened.

Several times they tried to negotiate a peace arrangement with the Han, but the Chinese were adamant that they became vassals.

In 48 AD the Xiongnu confederation again split in two, a southern and a northern half.

Within two years, the former submitted to the Han.

The north retained its independence and after 60 CE reconquered territory in the Tarim basin.

It took the Chinese general Ban Chao three decades and several campaigns to re-establish Han control over the area.

Total elimination took even longer; the last remnants of the southern Xiongnu were not subjugated until 216 CE.

During the war, the Chinese made good use of their vastly superior manpower, while the nomads exploited their own maneuverability.

Despite many victories in battle, it took the Han 2½ centuries to break the Xiongnu.

But their strategy to bring the north into their sphere of influence was sound and laid the foundations for later Chinese dominance over the area.

Nonetheless the war brought neither side much immediate gain, as for a vey long time neither could decisively beat the other.

The nomads were not powerful enough to take on the vast armies of the Han; the Chinese could not conquer Mongolia because there was nothing to conquer there.

In the end the Han finally destroyed the Xiongnu, but the dynasty itself ended only a few years later.

Ironically, for the next four centuries northern China would be ruled by men of non-Chinese origin.

War Matrix - Han-Xiongnu War

Roman Ascent 200 BCE - 120 CE, Wars and campaigns